This story originally appeared in the February 1998 issue of READ magazine. Learn more about the story here.

Corey had always been there, and she had always been strong. When Morgan’s parents got divorced, she had been there. When he went into regenerative nerve surgery after falling from a tree, she had been there. She was always willing to help, because she was Corey, and nothing ever bothered her for long.

Morgan approached her house. As always, he crawled over the banister and rang the doorbell. Corey’s freckled face appeared behind the window. She opened the door and said nervously, “Hi.”

“Hi.” Morgan stuck his hands in his pockets. “Do you mind if I come in?”

Corey frowned a moment, then opened the door wider.

Morgan entered the large quiet house. His feet shuffled against the hardwood floor. “Are your parents home?”

“They’re in Switzerland, all week.” She glanced back at him over her shoulder as she closed the door. “Are you still mad about what happened last time?”

Morgan grimaced and looked away. “No,” he said. “Actually, I was thinking we should just pretend it never happened. It’s not worth ruining a friendship over.”

Corey gave him a relieved smile.

“You know,” he continued, “just forget about it.”

Corey’s smile vanished. She eyed him with uncertainty.

“What?” he said. “It’s just a figure of speech — ‘forget about it.'”

Corey shook her head. “No. Not anymore. Nobody just forgets about stuff anymore, not since memory chips. Your choice of words makes me wonder, Morgan. Did you really forget about it? Did you erase those memories?”

“Of course not,” he said.

“Well, what happened, then? Tell me, what happened the last time you were here?”

Morgan sat down at the bottom of the stairs. “I don’t want to talk about it.”

“Don’t give me that,” Corey said. She waited.

Morgan was silent a while. Finally, he threw up his hands. “All right. Fine. You like watching me squirm? I did it. I erased the memory. I don’t remember our argument.”

She glared at him. “You really are something, you know?” She turned and stomped into the living room. “You come over here and start spouting about forgiveness and not spoiling our friendship, and you don’t even remember what our argument was about! Why didn’t you just tell me you erased the memory?”

“Because I knew you’d get angry,” he shouted, following her. “Like you always do. When I erase something.”

She turned on him. “Why did you do it, Morgan?”

He sat on the floor and leaned his back against the couch. “Why does anyone? I don’t want to have to remember all the shitty little things that happen to me.” He sighed. “What’s the point of having memory chips if you can’t use them selectively?”

Corey said, “They were supposed to be for perfect long-term memory.”

“Well, at least I keep the memories of the erasure,” Morgan said. “Most people don’t even do that. They erase every trace, like nothing ever happened. That’s dangerous. What I do just makes life easier to deal with.”

“Any memory erasure is dangerous,” she said.

“If it were really that dangerous, it’d be illegal.”

“It will be,” she replied. “Soon. When the bill comes up for a vote next month — ”

“It’ll get voted down, just like the last time. Face it, Corey, nobody really wants it to pass. Everybody erases, even people in Congress.”

“Don’t you remember what Mr. Brottenberg said?”

Morgan laughed. “Brottenberg? He does it too.”

Corey’s face froze. “No, he doesn’t. He wouldn’t. I mean, not after everything he says in class.”

“He erases memories, including those of the erasure. That’s why he acts so proud of himself. He doesn’t even know he’s done it.”

“That’s not true! You’re just trying to change the subject.”

Morgan leaned back and sighed. “Look, I’m sorry. I just don’t want to remember hurting you. Is that so wrong?”

Corey pouted. “I guess not. But I don’t approve.”

Morgan smiled faintly. “I know.”

They sat together awhile, silently staring out the window. Finally, Morgan asked, “So what was it? What was our argument about, anyway?”

Corey’s voice was half sardonic, half serious. “Why don’t you just forget it?”

Mr. Brottenberg sat at his desk, his dress shoes propped on the chair in front of him. “An idea that was commonly quoted around the turn of the century was ‘All the world’s libraries on a computer chip the size of your thumbnail.’ So it was only a short time before people realized the incredible potential of implanting such a chip into the human brain.”

“Of course,” he continued, “the chips are really much smaller than your thumbnail.”

Corey raised her hand. “How do you feel about erasing memory chips? Do you think it’s right?”

Mr. Brottenberg frowned. “I hope I’ve made it clear that I certainly do not approve of it. If everyone were allowed to purge all unpleasant recollections, the potential implications — for both the individual and society — would be extremely serious. That exact dilemma will constitute a large portion of our classroom discussion this year –”

Corey cut him off. “So you would never do it yourself?”

“Of course not.” Brottenberg’s usually calm face was tinged with indignation. “And I urge all of you not to do it, either. The consequences can be devastating.”

Across the classroom, Corey gave Morgan a meaningful look. Mr. Brottenberg went on, “I always tell my students: memory erasure is bound to get you into trouble. Even unpleasant memories are vital for shaping our character and our actions.” He paused. “And there are other dangers, too. Sometimes people get so upset that they erase all their memories: they have to relearn everything — how to walk, how to talk. It ruins their lives.”

The bell rang. Immediately the room filled with the din of footsteps and scraping chairs. Morgan stayed seated and raised his hand.

“Yes?” Mr. Brottenberg said. Some of the other students paused.

Morgan asked, “Has that ever happened to any student of yours?”

Corey stared at him in shock. There were stories whispered in the halls. Everyone knew about it.

Mr. Brottenberg was unperturbed. “No. Fortunately, no students of mine.” He sighed. “I know colleagues who’ve lost students like that. It was devastating for them, very difficult to deal with.” His face betrayed no hint of comprehension.

Morgan returned Corey’s stare, but she looked away in anger.

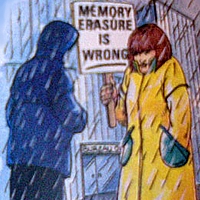

A few days later, Morgan was walking downtown. He spotted Corey standing on a curb. It was raining, and a hard wind was blowing. Corey struggled to keep a grip on the poster she was holding.

Morgan approached her. “What are you doing out here?” He squinted at the poster. The rain had made the colors run. He read, “Memory erasure is wrong.”

Corey looked at him miserably. Her clothes were soaked. She said bitterly, “I’m holding a rally.” She pointed across the street. A small office, the Bureau of Neuroelectronic Improvement, crouched between a bank and a supermarket.

“By yourself?” he asked.

“I talked to about twenty people,” Corey said. “They promised to be here around three.”

The clock on the chip in Morgan’s head told him it was 3:42. He said sympathetically, “Must be because of the rain.”

“I feel so stupid,” she said, “having a rally by myself. Rallies are supposed to be, you know — loud, with chanting and sign waving and hot dogs, and all that.”

“Rallies don’t do any good,” Morgan said. “There’s usually only one person who really cares. The rest just show up for the chanting and the sign waving and the hot dogs. They wouldn’t stand in the rain.”

Corey was silent.

“If you want,” Morgan added, “we could go back to my house and make hot dogs. Hell, we could even chant, if you want.”

That made her smile a bit, but she said, “No thanks. I’m staying.” She looked at him. “You’ll stay with me, won’t you?”

“I don’t believe in your cause,” he said. “Memory erasure helps people. It helps them cope — ”

“You don’t have to believe,” she interrupted. “Just stand here. Just keep me company.”

“I’m sorry, Corey. I leave when it rains. I’m one of those people.”

She said softly, “No you’re not.”

Morgan didn’t know what to say. So he stayed, in the rain.

A few minutes passed. “If you want,” Corey said, “I have another poster. I stuck a few under that bush so they wouldn’t get wet.”

Morgan shrugged, then chuckled. “Why not?” He dug out a damp poster and held it up. He nodded at the small office across the street. “Why are you rallying here, anyway? They don’t manufacture the chips here. They don’t make the rules.”

“I don’t know,” Corey said. “I thought maybe if I could just convince one or two employees, they could talk to the developers, convince them to make chips that can’t be erased.”

The rain got heavier.

“This is a total waste,” Corey said. “The whole afternoon standing out here, and what did I accomplish?”

Morgan offered, “I thought I saw someone glance out the window.”

Corey lowered her poster. “It’s just so frustrating. I want to make a difference, but there’s nothing I can do. How can one person make a difference?”

Morgan said wryly, “Do something illegal. That’s the only time people pay attention.” He took her by the elbow. “Come on. I’ll make you some hot dogs.”

Late that night the phone rang. Morgan was sitting in the kitchen eating leftover dessert. He picked up the phone.

Corey’s voice whispered, “I did it.”

Morgan was confused. “Did what?”

“Something illegal.”

Morgan leapt to his feet. “Jesus, Corey, it was a joke!”

“I hacked into the computer at the bureau,” she said. “I thought I might find something incriminating — chips malfunctioning, health hazards, anything.” She fell silent.

Morgan waited. Finally, he asked softly, “What?”

“Something awful,” she said. “Horrible.” She sounded upset, like she was crying.

“What’s wrong?” he said.

“When someone erases a memory, their chip transmits a copy to the bureau. They keep everyone’s erased memories.”

“Why?” Morgan said. “Blackmail?”

“I don’t know.” She was almost sobbing. “I feel so mixed up now. I was looking through the files of people I know … ”

Morgan cringed. “Mine?” he asked nervously. “Did you look at mine?”

“I looked at mine!” she said.

Morgan frowned. “I don’t understand.”

“Mine, Morgan! My memories! The ones I erased. I did what you don’t do. I erased my memories of the erasures. Because I didn’t think I could live with myself if I remembered. But now I do.”

Morgan stared at the phone in stunned silence.

Corey kept going. “My sister Kara … ”

“What about her?” She had died years ago. Corey never talked about her.

“I didn’t remember her,” Corey sobbed. “My own sister! It’s so awful. I can suddenly remember all these bad, shameful things, and it’s like they all just happened.”

Morgan shook his head. “You know, it’s funny. I used to really respect you. I envied you. Things happened, and you just shrugged them off, like you could handle them. But you couldn’t really, could you?” He tried to keep the bitterness out of his voice. “And to think, you were the one who was always arguing so hard for people to have to live with their memories. You erased yours just like everyone else, but you were too stuck up to admit it to yourself.”

“Morgan.” Her voice was weak. “Don’t do this to me. I didn’t know!”

He said flatly, “It’s just a big disappointment, that’s all.”

The phone went dead. He cradled it against his forehead. Wrong thing to say, he thought.

He quickly called Corey back, but there was no answer. He ran his fingers through his hair. Corey’s parents were out of town. She was alone, in a dark empty house, with a lifetime of bad memories beating down on her — and a brand new one that was all his fault. He cursed.

He called again. Still no answer. She was probably fine, he thought, probably just ignoring him, thinking about all the nasty things she was going to say to him. Or maybe she wasn’t.

He ran out the back door. His feet were bare, and the cold grass tickled as he sprinted across the lawn. He remembered all the good times with Corey — picking apples in autumn, swimming in the lake, walking in the woods. Those memories were forever etched in silicon on a tiny chip in his brain.

He followed the familiar path through the trees. As he approached Corey’s house, he saw that the windows were dark. He vaulted over the banister and tried the front door, but the corner stuck. He took a step back and slammed it with his shoulder. The door came open, and he stumbled into darkness.

“Corey!” he called. He made his way across the hardwood floor and into the living room. The television was on. Corey was curled up on the couch. Blue-white light flickered over her face.

Morgan sighed with relief. He laughed nervously. “Corey. I just wanted to see how you were doing. Listen, I’m sorry about what I said.”

She turned her eyes slowly toward him, but didn’t answer. Morgan frowned, and took a hesitant step forward. “Are you all right?”

Her wide eyes watched him curiously. He stretched out his hand to her. Corey reached out and gently clutched his finger. He tried to withdraw his hand, but she wouldn’t let go. He studied her. “Corey, talk to me.”

Her eyes were innocent and inquisitive, eyes that were new to the world. For a moment Morgan stared in confusion. Then he understood. “No,” he murmured. “Oh God, no.”

She opened her mouth, but all that came out was a meaningless coo. Baby talk.

“Corey, no!” He wrapped his arms around her and held her. A few of his tears fell silently on her shoulder. She explored his face tentatively with the tip of her finger. She poked him in the eye.

A few days later, Corey’s mother showed up at Morgan’s door. She had been pretty once, but now she looked tired and miserable. She wore too much makeup.

“Morgan,” she said, “I know that you know what happened to Corey.”

Morgan didn’t answer. He turned and retreated into the house. Corey’s mother followed him. “Someone’s been feeding her while we were in Switzerland. It was you, wasn’t it?”

Morgan sat down on the couch and stared off into space.

“Morgan, please. I’m not blaming you. I’m not going to press charges or anything. I know it wasn’t your fault. It’s just that, as a mother, I have to know. What happened to my daughter? Why did she do such a thing? Why would she possibly do it?”

Morgan turned to her. He looked her straight in the eye. “I forget,” he said.