This story originally appeared in the July/August 2003 issue of Cicada. The illustration is by Nathan Hale. Learn more about the story here.

Berlin on April 26, 1945 was a ruined husk of a city. The buildings were empty, scorched, and roofless. Rubble fell from crumbling walls and littered the quiet streets.

A group of men popped suddenly into existence. They wore heavily armored gray suits and carried advanced weaponry and equipment. The letters U.N. were printed in blue on their shoulders. Through clear face plates they studied the broken city, and the overcast sky.

Debris crunched beneath their heavy boots as they marched. They came to a bunker and blasted open its doors with explosives. Inside, startled German guards cried out and opened fire with rifles, but the shots bounced harmlessly off the men’s gray armor. Bullets ricocheted away into the darkness, and the U.N. soldiers stomped past, unconcerned.

They went down into the deepest corner of the compound, where a slight man with a narrow brown mustache sat. He tried to shoot himself, but they grabbed him, wrestled the pistol away from his mouth, and handcuffed his hands behind his back.

“Herr Hitler,” said one of the U.N. men. “Sie mussen mit uns kommen.”

Another man said, “You have been indicted by the war crimes tribunal at the Hague for crimes against humanity.”

They zipped Hitler into a silvery body bag. One of the U.N. soldiers opened a compartment on his own wrist and pulled the bright red lever inside. There was a moment when the universe seemed to be all strange and wrong, and then the men were gone.

* * *

Sol Erikson, Special Representative to the United Nations war crimes tribunal, sat in his kitchen eating breakfast. Through large bay windows, he could see the snow-capped peaks of the Alps.

His wife, Cassie, deactivated her newspaper. “You didn’t tell me you were going to execute him.”

Sol shrugged. “I told you we were going to ‘bring him to justice.’ What did you think we were going to do?”

“He died more than a century ago, Sol. What’s the point?”

“He was one of history’s greatest monsters. He murdered millions of people, and was never punished for it.”

“He killed himself, in the end. That’s not punishment?”

“No,” Sol said. “It’s not the same. We’re bringing him before a court of justice. He’ll be informed of the charges against him and made to answer for them. That makes a lot of people feel good, and I’m not ashamed to admit that I’m one of them.”

“But it doesn’t change what happened?”

“The past can’t be changed. That’s the nature of time travel.”

Cassie shook her head. “I’ve never understood that part.”

“All right, look.” Sol took out a pen and drew a long blue line on his paper napkin. “Just think of this line as the timeline. Here we are — ” He marked a spot. ” — in 2083.” He marked another spot. “Here’s 1945. In our timeline, Hitler killed himself, the war ended and so on, up to the present. When we sent our soldiers back, that created a second timeline.” Sol drew a second line, which branched off the first at 1945. “In this new timeline, our men appeared in Germany in 1945 and arrested Hitler.”

“So you can change history. At least, in the new timeline…?”

“Well…” Sol paused. “No. Not really. You see, this new timeline is only temporary. It only exists as long as our time travelers keep pumping energy into it. Once they come home, it collapses — ”

” — And nothing’s different,” Cassie concluded. “Our timeline is still the same.”

“Right.”

She repeated, “So what’s the point?”

“Well, we can still bring people back with us out of this second timeline, and punish them. We’re sending a moral message: crimes against humanity will be punished no matter where — or when — they occur.”

“Fine,” Cassie said finally. “Punish him, then. I still don’t see why you have to execute him.”

“He’ll go to the annihilation chamber,” Sol said. “It’s painless. Besides, do you know how much an operation like this costs? These historical criminals will all be executed. All of them. If they’re not worth executing, they’re not worth retrieving in the first place.”

Cassie frowned. She didn’t say anything for a long time. Finally, she asked, “Why was Hitler first? Stalin killed more people.”

Sol shrugged. “There’s some politics involved, naturally. Actually, I shouldn’t even be telling you this — it’s still confidential — but don’t worry, Stalin’s next on the list.”

“Terrific,” Cassie said flatly.

Sol said wryly, “This is just the beginning.”

* * *

It was a cold autumn afternoon, five years later, when Cassie stormed into the kitchen. “Thomas Jefferson? Thomas Jefferson? You have got to be kidding me!”

Sol leaned back in his chair and studied his wife cooly. “The man owned slaves, Cassie. Those poor people were treated like animals. If that’s not criminal, I don’t know what is.”

“He lived three hundred years ago. Lots of people owned slaves back then.”

“So lots of people were doing it. That doesn’t make it right. A man of his intelligence and character should have known better. The slave trade was an affront to human dignity. We can’t just let it pass.”

“But Thomas Jefferson was a great man.”

“Great in some ways,” Sol conceded. “Deeply flawed in others.”

“We’re all deeply flawed,” Cassie said. “Why couldn’t you pick someone else? Some really rotten guy who separated families and beat his slaves.”

Sol shrugged. “There’s some politics involved, of course. A lot of people are angry about how the American forefathers have been glorified — the same forefathers who owned slaves. We’re sending a message: famous people don’t get special treatment.” He paused. “George Washington would’ve been an even bigger coup, but he’s too symbolic. The U.S. has a lot of things named after Washington. Jefferson is well known to the general public, but they’re not overly attached to him.”

Cassie groaned. “Since when is it a crime not to have people be overly attached to you?”

“You’re avoiding the issue, Cassie. Thomas Jefferson participated in the brutal exploitation of innocent people. His finer qualities don’t excuse that. Nothing does.”

* * *

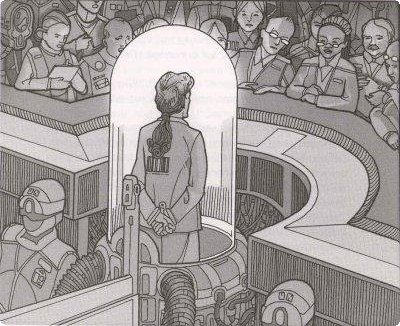

Thomas Jefferson was red-haired and sad. He faced his execution stoically. Dressed in a faintly shimmering yellow prison uniform, hands bound behind his back, he was led to the annihilation chamber. A crowd of lawyers and officials, including Sol, had gathered to witness it. Standing there behind the glass, Jefferson’s sorrowful eyes caught and held Sol’s.

The loudspeaker buzzed. “Do you have any last words?”

Jefferson’s voice was slow and soft. “I don’t understand this place. I am sorry, for the wrongs I’ve done. I–”

“That’s enough,” the loudspeaker said.

Sol and Thomas Jefferson stared at each other through the glass. Jefferson’s expression was one of — what? Regret? Or even pity? Why?

The technician flicked a switch. The annihilation chamber was suddenly empty. There was no more Thomas Jefferson.

Sol turned to the technician. “You could have let him speak a little longer.”

“This is on television,” the man said. “We don’t want to make a martyr out of him. Keep people focused on his crime, that’s what we’ve got to do.”

“Yes,” Sol said. “I suppose.”

* * *

A few months passed. One night, Sol answered his door to find a detachment of U.N. soldiers camped on his doorstep. They wore heavy gray suits.

“Solomon Erikson,” said one of them. “Come with us, sir.”

Sol hung back in the doorway. “Is there a problem?”

Cassie sat at the kitchen table, watching worriedly.

“Sir,” the man repeated. “You have to come with us right now. Every moment we stay here is costing the taxpayers millions of dollars.”

Sol stared at the man. “You mean you’re–?”

“Yes, sir.” The man nodded, and took Sol by the arm. Two soldiers stepped forward and handcuffed Sol’s hands behind his back.

Sol demanded, “What’s going on?”

They wrapped him in a silvery bag. “Sir, you’ve been indicted by the war crimes tribunal at the Hague for crimes against humanity and nature.”

“No!” Sol shouted, squirming and kicking inside the dark sack. “No!”

* * *

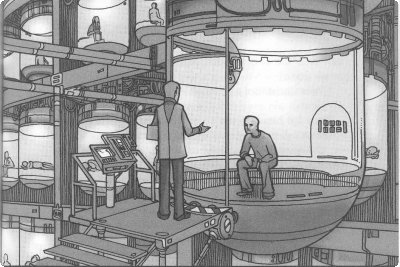

Sol’s prison cell was clean, well-lit, and made of some sort of translucent plastic. There were no metal bars, but he got an electric shock if he moved too close to the doorway. Sol sighed and pressed a button. Part of the wall ran like melted wax, forming itself into a cot for him to sit on. Sol sat, and stared at the floor.

“Hey!” a soft voice hissed. “Hey! Look up!”

Sol looked up.

A young man, perhaps twenty, stood just beyond the doorway. “Mr. Erikson, it’s a pleasure to meet you.”

“Who are you?”

“Me?” the young man said. “I’m nobody. Just a paralegal. I’m not supposed to be here, but I couldn’t resist. I’m a huge fan of your work — the prosecution of Jesus Christ. That was brilliant, absolutely brilliant.”

“What?” Sol said. “I — ”

The young man frowned. “They must have pulled you from before that. It’s always a little tricky, deciding what age to pull someone.” He thought for a bit. “You can’t pull them before they’ve committed their crimes, of course. That’s not legal. But if you wait too long, well, people get squeamish about sending old men to the chamber — ”

Sol interrupted, “We executed Jesus Christ?”

“Of course.” The young man looked surprised. “History’s biggest monster.”

Sol looked on, mystified.

The young man said, “Christ was responsible for more death — indirectly — than anyone else in history. Of course, it took some social evolution before we were able to see that clearly.”

“How far in the future am I?” Sol asked.

The young man bit his lip and stared at the ceiling. “They must’ve pulled you from, let’s see — I’d say about eighty years ago, give or take.”

“I never committed any crimes,” Sol said. “You have to do something. I’m innocent.”

The young man shook his head. “Oh, come on. We don’t make mistakes here. You know that. Still, they only chose you for political reasons. The tribunal has to demonstrate to the decentralists that even their own ranks are subject to purview.”

“Demonstrate to who?”

The young man grimaced. “I hate to be the one to tell you this, but there’s a strong coalition allied against you: universalists, populationists, samaritanists. Of course, they wouldn’t have indicted you if they weren’t sure of a conviction.” He sighed. “But I don’t have to tell you that.”

“What are they charging me with?”

“No one’s told you? I guess they’re saving it for the trial. Some bad stuff. Not so bad in your own day, I guess, but someone like you — ” The young man’s face was sad and disappointed. ” — you really should have known better.”

The young man glanced over his shoulder. “I better get going. I’ll be watching at the trial, though, and the execution.”

“Wait!” Sol shouted, rushing forward. “I don’t understand. Wait!”

The doorway gave Sol a sharp electric jolt, and he fell back onto the cot. It didn’t matter. The young man was already gone.

“Jesus Christ,” Sol exclaimed.

* * *

They led him into the courtroom and sat him down at a desk. A tall podium rose up before him, forming a wide arc. The room had changed, but was still eerily familiar: the tribunal.

“Soloman Erikson,” the chairman said, “at this inquiry you will be informed of the charges against you and given the chance to make a statement.”

“I understand, Mr. Chairman,” Sol said.

“The first charge,” the chairman intoned, “is that you participated in the exploitation of living beings for the purpose of consuming their flesh.”

Sol was confused. “Living beings?”

“Living beings, sir,” said the chairman. “Pigs, chickens, cows — ”

“I — I did eat meat, yes. Is that — ?”

“The second charge,” the chairman added briskly, “is that you had two children of your own.”

“Yes,” said Sol. “Yes. Two little girls.”

“Mr. Erikson, you were aware that the Earth was becoming dangerously overpopulated?”

“I don’t — I mean, I guess I’d heard — ”

“And with full knowledge of this, you continued to have children?”

Sol nodded weakly.

“The third charge: you, knowing full well of people who needed your help, did not aid them.”

“I gave money to charity,” Sol insisted.

“You lived in needless luxury, in a large house in the mountains, while all over the world people died in poverty.”

“This is crazy!” Sol exclaimed.

“Mr. Erikson, you are found guilty of the charges against you. You are sentenced to death by annihilation.”

“This isn’t right!” Sol shouted. “You’re not judging me, you’re judging my society!”

“Mr. Erikson,” the chairman said. “The fact that other people were committing the same crimes does not in any way mitigate or excuse your own guilt.”

Stern-faced guards led Sol from the room. He was given a meal, dressed in a slightly shimmering yellow uniform, and led to the annihilation chamber. Through the glass, the young man, the paralegal, watched Sol grimly.

The loudspeaker buzzed, “Last words.”

Sol stared at the young man. “Watch out, kid. Watch out that they don’t get you.” He turned his eyes to the ceiling. “Cassie, I — ”

“That’s enough.” The technician reached for the switch.

Sol watched, terrified, as the hand moved closer … closer … as the switch began to fall —

Sol cringed. Then he was gone.